Design Thinking: New Challenges for Designers, Managers and Organizations

International DMI Conference 14-15 April 2008, ESSEC Business School, France

Raija Siikamäki Fiskars Iittala Group, P.O. Box 130, 00561 Helsinki, Finland

Nina Seppälä UCL University College London, Gower Street, WC1E 6BT, UK

Raija Siikamäki graduated from the University of Art and Design Helsinki with a Master of Arts degree in 1992 and with a Doctor of Arts degree in 2006. She has worked in her alma mater as a researcher and part-time teacher between 1993 and 2002. Her research interest lies in the areas of environmental issues in design business and research. She graduated from Kingston University with MBA degree in 2007 and works at the moment as a research manager for Fiskars Iittala group.

Nina Seppälä holds a PhD from Warwick Business School. Her research interests lie in the areas of stra tegic management and corporate social responsibility. In the area of strategic management, she is study ing the concept and development of strategy in non-profit organisations, especially the agencies and mis sions of the United Nations. In the area of corporate social responsibility, her research focuses on explor ing and framing the boundaries of responsibility between companies, states, and individuals. She cur rently works for the Department of Management Science and Innovation at University College London.

Abstract

Design industries are facing the challenging situation to improve their environmental performance. The focus has mainly been on making the practices of existing enterprises more environmentally friendly, but a growing amount of companies has had an environmental commitment as a starting point for their business activities. However, only a few studies have focused on these businesses. This comparative case study aims to fill some of this gap by exploring the special features and strategies of three micro-size, United Kingdom based design enterprises that use recycled materials in their products. The underlying assumption was that the cases would bring out unique features from eco-design companies – features not common to the small and micro scale enterprises in general.

It was found out that the studied micro-size design companies were entrepreneurial and used design in an innovative way. As is typical for the young and/or small organisation and entrepreneurial strategy, the owners had the control leading the companies with personal vision. Entrepreneurial strategies were deliberate: this type of strategy is characteristically flexible, creative and having first-mover advantage. The studied companies had successfully passed the first life-cycle phases of small companies. All of them viewed growth as an important objective. While growth was important, it was not pursued at the expense of environmental or design considerations. Further, the quality of design was seen as a characteristic that should not be compromised because of environmental or economic aims. The study therefore suggests that even though ecopreneurs may be classified according to their desire to change the world and desire to make money, the latter is only pursued if the former is satisfied. From the prioritisation of design and environmental values follows that growth was not only evaluated in economic terms. Influence on the market was identified as a sign of success e.g. direct competition was even welcomed when it was seen to promote the values of the company. Moreover, the studied companies did not analyse their business in relation to that of competitors, but their own values and expectations of growth. Design expertise was an important asset for the companies studied and it formed the basis of their differentiation strategy. The differentiation strategy was based on the advocacy of certain values and ways of thinking rather than the anticipation and accommodation to customer needs and desires. However, demand has this far exceeded supply.

Introduction

During 1960’s and 1970’s there were initiatives against the modern manufacturing methods and con sumption behaviour. In early the 1990’s designers adapted these principles of Design for Environment (DFE) (Mackenzie 1997). Various terms, such as terms ecodesign, sustainable design, life cycle design and green design the have been used depending on the tradition from which they developed, to describe a phenomenon which is understood to be a systematic integration of environmental considerations into design process across the product life cycle (Bhamra 2004, Charter and Chick 1997).

Both external and internal influences can be driving organisations towards implementing ecodesign. Bhamra (2004) identifies the following ones: cost savings (eg. less material used), legislative regulations, competition, market pressure, industrial consumer requirements, innovations (e.g. new market op portunities by integrating environmental issues to the product development), employee motivation, cor porate social responsibility and communications. According Bhamra (2004) approaches to ecodesign can incremental or innovative. Incremental approach uses exiting products, business models or forms and incorporates environmental issues to those. The innovative approach uses environmental considerations as the driver for new concepts. As Bhamra describes, it can be viewed “as a marriage of technology, culture and nature” which deals with innovation, creativity and effectiveness. Also cultural and lifestyle factors are important for this multidisciplinary approach. An innovative approach is more likely to achieve targets set to the environmental performance but this approach is little understood and practised (ibid.).

Van Hemel (1998) and Brezet (1997) proposed a series of ecodesign strategies and principles described as a wheel of Life-cycle design strategies (LIDS). This wheel is a collection of descriptions from various thinkers and “it is to provide an exhaustive overview of the options for improving the environmental profile of a product throughout the different stages of its life cycle…”. Van Hemel classifies ecodesign strategies as the following: selection of low-impact materials (eg. recycled materials), reduction of material use, optimisation of production techniques, optimisation of distribution system, reduction of impact during use, optimisation of initial lifetime, optimisation of end of life and new concept development. This integrated tool aims to represent strategies from both the incremental and innovative approaches to ecodesign. The principles and strategies are represented as a directional wheel in hierarchical order, which relates to the various stages of the product development.

The recent study, Richardsson et al (2005) identified as drivers for sustainable design practices among UK designers to be the following: competitive or economic advantage, regulations, market and consumer demand, personal motivators and alignment of ethics with profession. The willingness for mate rial reuse among UK designers and architects was studied by Chick and Micklethwaite (2003, 2004). Findings identified that there are obstacles, such as lack of information, unfamiliarity, supply of recycled materials, costs related to the recycled materials use, concerns related to the quality, practical constrains and concerns about the markets for products made out of recycled materials. Recycling is part of the linear product process chain in the product lifecycle. The material product has a lifecycle of sequences of processes in a product’s life: production, consumption and waste processing. Steps in products process, include the production phase, subdivided into three subsequent steps: material production, parts production and assembly. After consumption and possible repair, product are dismantled, separated and discharged. The linear product process chain can contain three different steps of reuse: re-use as a product, parts re-use and material recycling. When materials are considered, waste is generated in the production process and part of materials becomes waste at the end of the product lifecycle. (Lambert 2001, Stead and Stead 1992, McDonough and Braungart 2002).

Recycling, reverse logistics, of complex products gives diverse challenges. This have been defined by “Seven Rights”: ensuring the availability of the right product, in the right quantity and the right condition, at the right place, at the right time, for the right end-user, at the right cost” as cited by Martin (2001).

Research approach and design

A qualitative research design was applied to pursue the exploratory aims of the study. The findings are based on interview and document material collected from three London-based design companies. Each company was treated as a case in line with Yin (1994) and Eisenhardt (1989). A pool of companies using recycled materials to create design products was identified through a survey of literature and public organisations working in related fields. As a result, 18 companies were found. Half of them operated in the fashion business and their products involved the recycling of diverse materials including textiles, glass and plastics and/or recycling of products or their parts like clothes, tyres and computer chips. After an elimination of some of the companies based on similarities in business concepts, ten of the companies were contacted via e-mail to inquire about their interest to participate in the research. In the end, three companies were included in the study.

As seen in Table 1 below, the companies share number of characteristics beyond the use of recycled materials and focus on design.

Table 1. Comparison of case companies

|

Company 1 |

Company 2 |

Company 3 |

| Established |

2003 |

1997 |

2000 |

| Employees |

2 + project workers |

5 + project workers |

2 + project workers |

| Production |

Design in the UK; manufacturing in China |

Design and manufacture in-house in the UK |

Design in the UK; manufacturing in the UK and Spain |

| Sales channels |

Stockists, Internet |

Own shop, Stockists |

Major department stores, Internet |

Interviews were identified as the main source of information (Kvale 1996). They were held in September-November 2006; and took a semi-structured form because of the exploratory nature of the research (Fontana & Frey 2000). The questions were designed to gear the discussion towards strategic topics such as drivers to start the business, objectives of the company, key challenges, management of demand and supply, growth, rivalry and performance.

Views on future trends were also sought. Interview data was first studied within each case and then across cases. The cross-case examination involved the identification of similarities and differences between cases so that propositions going beyond the characteristics of a single case could be formulated (Eisenhardt 1989).

Business concept and strategy

An interest in producing environmentally friendly design products was, in some form, a starting point for each of the three companies studied. Some found recycled materials as a source of inspiration, while others had identified an increasing demand for environmentally friendly design products. The design aspect was given particular significance: products had to be “cool” and “beautiful” and noted for that quality, not only for the underpinning environmental thinking. The quality of design was therefore seen as a characteristic that should not be compromised because of other aims.

All the companies pursued a differentiation strategy based on design and environmental thinking (Porter 1980). As is typical for this strategy, the companies had been first in their product categories to offer design items made from recycled materials and thus experienced usual first-mover advantages and difficulties. Expertise in design was an important asset for all the companies studied and it formed the basis of their differentiation strategy. The founders also had a strong personal commitment and interest in recycling and related technologies were developed to differentiate the products from other design products. The combination of ‘design’ and ‘green’ therefore provided a basis for differentiation within both product categories: environmentally friendly design products and designed green products. As will be discussed later, this mix appealed to two groups of customers and contributed to the success of the companies. Further, the combination of design expertise and ability to make use of recycled materials enabled the companies to develop their strategies from ‘inside-out’ as opposed to ‘outside-in’ which places the market and the competition as starting points for the strategy process (McGee et al. 2005). Strategy was therefore driven by a set of internal resources and values rather than external factors as suggested by the resource-based view on strategy (Wernerfelt 1984; Rumelt 1984).

The studied companies were highly entrepreneurial and the owner-managers led the companies with personal commitment and vision. This is characteristic for start-up companies that seem to need personalized leadership to establish their basic direction and strategic vision (McGee et al. 2005; Mintzberg et al. 1998). In all of the studied companies, leadership was visionary and, as is typical for a growth phase, also practical.

The companies did not analyse their business in relation to that of competitors, though one of them acknowledged the threat of competitors in the absence of barriers to entry. Even though the companies did not think about their products and strategy in relation to competitors, they all had rivals representing mainstream manufacturers and retailers. The lack of attention on competitors resulted from the perception that their own products were unique and thereby lacked direct competition. Further, as promotion of ethical consumption and the use of recycled materials were seen as important aims, competition was welcomed rather than approached in antagonistic terms: getting more entrepreneurs to adopt their business concept was viewed as a success from the viewpoint of environmental thinking.

The companies did not focus on long-term plans. According to Lasher (1999), SMEs are typically orientated towards the short-term. This focus is often due to a lack of resources: lack of time and possibly also lack of knowledge about how to plan for the long term. The importance of long-term planning in SMEs has also been questioned. Mintzberg (2005), for example, argues that “sometimes lack of strategy is temporary and even necessary…Eventually all situations change, environments destabilize, niches disappear. Then all that is constructive and efficient about an established strategy becomes a liability. That is why even though the concept of strategy is rooted in stability, so much of the study of strategy focuses on change”.

Mission to change society and competitors

All of the studied companies sought to influence the way in which recycled materials were perceived by consumers. This desire was expressed as an aim to “inform” and “change consumer perceptions”. The recycled products were experienced to have a stigma of being something less valuable than products made out of virgin raw materials. The companies sought to address this stigma by designing products that were both functional and aesthetically pleasing. Design was therefore used as a way to make recycled materials more appealing to the market. From this followed that the quality of design was not compromised at the expense of environmental or economic considerations.

The companies also sought to have an impact on their sector as a whole. As a result, adoption of their ideas by more established companies and the emergence of direct competition were welcomed rather than viewed as a threat.

“How can we change consumer perception? If what they buy, where they buy, where it came from, how it was made – all of that for me is really important…our company is small but we can have an influence in the market, that’s really our big goals. “

Nevertheless, the companies experienced some resistance in marketing their goods as the variation that recycled materials bring to the product was found to be obstacle for selling the products through some retailers that were used to standardized and mass-produced items. These retailers regarded variation as a fault rather than a sign of high quality. Some of the products were still sold through well-known retailers, while others were brought to the market via shops specialised in selling design and/or ethical products. All of the companies also used the Internet to sell their products. Further, the companies found it challenging to source sufficient amount and quality of recycled materials. Sourcing of recycled materials has been a major obstacle for designers and architects who have sought to use such materials (Chick and Micklethwaite 2003, 2004). As a result, some of the companies had developed technological solutions to address problems relating to the quality and durability of the products.

In sum, the companies studied therefore differed from other SMEs because of their uncompromising focus on design and environmental values. Because of this, they assessed their success not only in terms of demand, sales, and turnover, but also in relation to their influence on society. This influence was mainly interpreted as the perception that consumers have of the use of recycled materials, but also in terms of their impact on other businesses. As Shaper (2002) notes, green entrepreneurship is not only important because it provides new opportunities for businesses, but also because it can contribute to an overall transition towards a more sustainable business paradigm; Shaper referred to this as the “pull” factor of green entrepreneurship.

Growth without compromises

Growth was regarded as important by all the companies studied. It was generated by the expansion of the volume of production and/or the product portfolio. The companies paid special attention to environmental issues, such as the miles materials or products travelled, while seeking to expand production. For example, one of the companies that had outsourced its manufacturing to China was looking for an environmentally committed logistics company for reducing its overall impact on the natural environment. It was also looking for a manufacturer in the UK or Europe to decrease the need for long-haul transportation. The companies also found local sourcing an important aspect of their operations.

Nevertheless, growth was not pursued unconditionally. As already seen, the companies did not want to compromise the values of environmental thinking and design at the expense of growth. Moreover, growth was seen as a way to influence the market as illustrated by the following quote from one interviewee:

“I think it has to be with any successful project but how we do that…as long as we are not sacrificing our values, as long as with growth we can improve all of our ethical aims, we cannot loose sight on that. With growth we can grow our influence.”

The companies therefore viewed growth and influence on competitors as inherently interlinked. Their overall strategy is with regard to their aim to grow in economic terms and change societal values. Other trajectories are also possible, but they would involve some type of strategic failure to reach desired goals.

Growth was enhanced by the avoidance of some of the typical difficulties encountered by young companies. Marketing, which Lasher (1999) identifies to be one of the biggest problems for SMEs, wasn’t a challenge for the companies studied. Their products had reached customers with little marketing effort. The companies identified the word of mouth as the most important channel through which their products were advertised. What’s more, their growth was enabled by the Internet and other electronic communication tools that made the transmission of information fast. All of them had also benefited from the attention of the media and public organisations that had been interested in ecodesign products.

As a whole, the studied companies demonstrate that economic rationality is not the only factor that drives business. Linnanen (2002) studied ecopreneurs and categorised them on the basis of two factors: their desire to change the world and their desire to make money and grow as a business venture. According to the findings of this study, design companies that use recycled materials in their products could be typified as ecopreneurs. The desire to change the world and the desire to make money are both present in their expressions for why they are doing business. However, the findings of the present study suggest that one element could be added to Linnanen’s model: non-compromise in the quality of design while environmental and economic aims are pursued.

One of the companies had also reviewed its business concept as competition had increased by offering the customers an opportunity to bring in materials that could then be used for new products. This service was established to have a unique feature on the market after there had been followers to the company’s original concept. It had proved successful as customers enjoyed being included in the sourcing and production process. As Grönroos (1998) states, the image of the service provider has an impact on the overall perception of quality. In this way, the company was able to address the stigma that recycled materials have and strengthen its business concept.

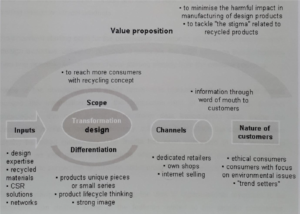

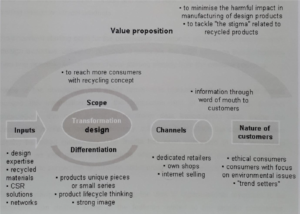

Figure 1. Common features of studied eco-design companies (adapted from the basis / as cited by McGee, Tomas and Wilson 2005)

The three studied micro size design enterprises each had features unique to them when comparing them with each others. These features were related mainly to structure and operations. However, it was possible to detect some special features common to the companies relating to value proposition, inputs, Value proposition, Transformation and Nature of customer. Values of manufacturing of environmentally sound design products and promoting recycling: by combining these aspects entrepreneurs believed in their ability to have an impact on consumer behaviour and to have an impact on the scale of this interest. With value proposition, the information about products with unique features had reached customers orientated to ethical consuming through word of mouth. They were served through own shops, dedicated retailers and internet selling.

Conclusions

This study explored the special features and strategies of three micro-size, United Kingdom based design enterprises that use recycled materials in their products. The underlying assumption was that the case study would bring out unique features from eco-design companies – features not common to the small and micro scale enterprises in general. In this explanatory, small-scale qualitative case study focusing on practice, the principles of grounded theory were adopted. The main source of primary data was interviews of companies’ key personnel.

It was found out that the studied micro size design companies were entrepreneurial and used design in an innovative way. Important starting points for the businesses were design expertise and utilisation of recycled materials. The owners had the control leading the companies with personal vision. Entrepreneurial strategies were deliberate and characteristically flexible, creative and having first-mover advantage.

The studied companies were already established in their fields and had successfully passed the fist lifecycle phases of small companies. Each of them viewed growth as an important objective and it was pursued through the expansion of the volume of production and portfolio of products. The growth strategies could therefore be seen as organic and low-risk. The analysis of the companies suggests that while growth is an important objective, it is not pursued at the expense of environmental or design considerations. All interviewers stated that the values of the company should not be threatened by growth. The companies had also taken action to ensure that the values were maintained. For example, materials were sourced locally and environmentally committed transportation companies were sought when one of the companies had manufacturing in China.

What is more, the quality of design was seen as a characteristic that should not be compromised because of environmental or economic aims. The study therefore suggests that even though ecopreneurs may be classified according to their desire to change the world and desire to make money, the latter is only pursued if the former is satisfied. From the prioritisation of design and environmental values follows that growth was not only evaluated in economic terms. Several interviewees identified influence on the market as a sign of success. The awareness that customers had of recycling was seen as particularly important, but influence on the products and practices of other companies were also seen as an indicator of success. This finding highlights the lack of relevance that some of the key concepts in the area of strategic management have for the analysis of ecopreneurs. Such basic concepts as ‘competition’ and ‘competitor’ appear particularly irrelevant for understanding the way in which ecopreneurs view their environment. Direct competition was even welcomed when it was seen to promote the values of the company. Moreover, the studied companies did not analyse their business in relation to that of competitors, but their own values and expectations of growth. Strategies were therefore planned “inside-out” opposite to the “outside-in” approach which places the market and the competition as starting points for the strategy process. Design expertise formed the basis of their differentiation strategy. As is typical for the differentiation focus, the studied companies had been first in their product categories to offer design items made out of recycled materials and thus experienced usual first-mover difficulties and advantages. Also typically to the differentiation strategy, the studied companies produced “unique products perceived to be superior in value”. The superior value was a created by a combination of design quality and ideological values.

As noted above, the basis of differentiation was sustained by the personal commitment of ecopreneurs to the values underpinning their business. The differentiation strategy was therefore based on the advocacy of certain values and ways of thinking rather than the anticipation and accommodation to customer needs and desires. This type of differentiation is possible when the values promoted by the company have appeal to a certain group of consumers and when the products are able to transmit certain meanings.

Finally, although the processing of materials requires detailed attention and the manufacturing process is labour-intensive, the companies were not particularly concerned about the followed pressure on pricing of their products. Demand has this far exceeded supply.

Acknowledgements

The writers would like to express their deepest gratitude to the entrepreneurs who gave some of their time in the midst of their busy schedules. It has been a great privilege to have an opportunity to talk about their businesses for this study, which was carried out at the Kingston University during academic year 2006-2007.

References

Bhamra T. A., Ecodesign: the seach for new strategies in product development, Proceedings of the I MECH E Part B Journal of Engineering Manufacture, Vol. 218, Professional Engineering Publishing, 2004

Brezet J. C., van Hemel C.G., Ecodesign: A promising Approach to Sustainable Production and Con sumption, UNEP, Paris, 1997

Charter M., Chick A., Editoral, Journal of Sustainable Product Design, 1(1), 1997

Chick A., Micklethwaite P., Specifying recycled: understanding UK architects’ and designers’ practices and experience, Design Studies, Volume 25 (3), May 2004

Chick A., Micklethwaite P, “Recycled tigers’ teeth?” Obstacles to UK designers specifying recycled products and materials, 5th European Academy of Design Conference, University of Barcelona, Spain, 2003. Available at: www.ub.es/5ead, [Accessed 6 May 2006]

Eisenhardt K. M., Building Theories from Case Study Research, Academy of Management Review, Vol. 14(4), 1989 Churchill N., Lewis V. 1983, The five stages of small business growth, Harvard Business Review, 61, May-June, 1983, pp.30-50

Grönroos C., Marketing Services: A case of a Missing Product, Journal of Business and Industrial Mar keting, 13 (3/5), 1998

Fontana A. and Frey, J. H., The Interview: From Structured Questions to Negotiated Text, in Norman K. Denzin (ed.) The Handbook on Qualitative Research, 2nd edition, Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks, USA, 2000

Hemel C. G. van, The IC EcoDesign project: results and lessons from a Dutch initiative to implement eco-design in small and medium-sized companies, Journal of Sustainable Product Design, Issue 2, 1997

Lambert A. J. D., Life-Cycle Chain Analysis, including Recycling, Greener Manufacturing and Opera tions – from Design to Delivery and Back, edited by Joseph Sarkis, Greenleaf Publishing Limited, Shef field, UK, 2001, pp. 36-55

Lasher W. R., Strategic Thinking for Smaller Businesses and Divisions, Blackwell, Oxford, UK, 1999

Linnanen L., An insider’s experiences with environmental entrepreneurship, Greener Management In ternational 38, Summer, 71–80, 2002

Kvale S., InterViews: An Introduction to Qualitative Research Interviewing. Sage Publica tions,Thousand Oaks, USA, 1996

Martin M., Implementing the Industrial Egology Approach with Reverse Logistics, Greener Manufactur ing and Operations – from Design to Delivery and Back, ed. J. Sarkis, Greenleaf Publishing Limited, Sheffield, UK 2001

McDonough W., Braungart M., Cradle to Cradle – Remaking the Way We Make Things, North Point Press, New York, USA, 2002

McGee J., Thomas H., Wilson D., Strategy: analysis and practice, McGraw-Hill Education, Maiden head, UK, 2005

Mackenzie D., Green design: design for the environment, Laurence King Publishing, London, UK, 1997

Mintzberg H., Ahlstrand B., Lampel J., Strategy Safari, FT Prentice Hall, 1998

Mintzberg H., Ahlstrand B., Lampel J., Strategy Bites Back, FT Prentice Hall, Harlow, 2005

Porter M. E., Competitive Strategy, The Free Press, New York, USA, 1980

Richardsson J., Irwin T., Sherwin J., Design & Sustainability – Scoping Report for Sustainable Design Forum, DTI, DEFRA and Design Council, 2005

Rumelt R. P., “How much does industry matter?”. Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 12, No. 3, pp. 167-185, 1991

Shaper M., The Essence of Ecopreneurship, Greener Management International, Issue 38, pp. 26-30, 2002

Stead E. W., Stead J. G., Management for a Small Planet: Strategic Decision Making and the Environment, Sage Publications Inc., Thousand Oaks, California, USA, 1992

Wernerfelt B., A resource-based view of the firm, Strategic Management Journal, Vol.5, pp.171- 180, 1984

Yin R. K., Case Study Research, Design and Methods, Second edition, Sage Publications, USA, 1994